A wilful pursuit of art over commerce and refusal to conform to the banalities of business has made Viktor & Rolf a rare breed in the fashion world: designers with the freedom to do things their way.

“We are best friends and our friendship is the basis of our work.” That’s pretty much the crux of the extraordinary 22-year creative force that is Viktor & Rolf. Viktor Horsting is speaking with L’Officiel on the occasion of the tenth anniversary of the label’s seminal fragrance, Flowerbomb. Alongside his partner in crime, Rolf Snoeren (“a genius”), Horsting has built one of the most provocative, nonconformist brands in fashion.

The pair, now in their forties, have known each other for most of their lives. They met while studying fashion at the ArtEZ Academy of Art & Design in Arnhem, the Netherlands. Renowned for being as thick as thieves, Viktor & Rolf is a tight creative unit. They established an instant rapport. “We’ve gotten to know each other really well over the course of the years. And I think the secret is … hmm, I don’t know. We like each other,” Horsting laughs. “We have fun, we respect each other and it has been like that from the beginning. [Our closeness] is really normal to us but to other people it’s sometimes bewildering.”

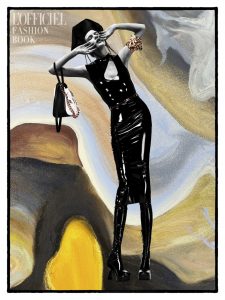

At the time of the interview, the clock is ticking until Viktor & Rolf take to the Parisian haute couture runway for the first time since announcing in January that, like Jean Paul Gaultier before them, they would abandon ready-to-wear to focus on high-end creations. “We enjoy that much more,” Horsting says simply. Citing superstition, Horsting won’t be drawn on what to expect from the collection except to say it’s “really in the line of what we’re talking about, the art of fashion”. When it’s unveiled 13 days later, the collection is a quite literal marriage of the two, with models appearing for all the world as though they had fallen through a masterpiece: wrapped in canvas with frames forming cuffs and collars. As models completed their walk, the designers themselves removed the creations and reconstructed them into artworks hung behind the runway.

Viktor & Rolf’s retreat from ready-to-wear is fitting for a label that, particularly in its early years, was better known for creating a stir and enthralling the media without doing much in the way of actually selling clothes. “We didn’t really know how to fit in to the fashion system,” Horsting admits.

After setting out together post-graduation in 1993, the duo won a design competition and relocated to Paris where they spent the next five years experimenting. Their bold stunts and conceptual designs garnered much attention, from metallic gold gowns suspended from the ceiling of a gallery to the launch of a ‘fragrance’, Le Parfum—complete with a lid that couldn’t open, a sly commentary on fashion branding (it sold out). Their first couture show in 1998 finally brought them into the industry fold. “We had a strong link to the art world in the beginning, we showed a lot in museums and galleries,” Horsting says. “To start showing couture was a logical step, let’s say, from the art world to couture. Couture and art, it’s really closely related.”

Ready-to-wear followed in 2000, menswear in 2003 and, the same year, a contract with L’Oreal planted the seed for Flowerbomb, which took two years to develop. Considering the irreverent statement behind Le Parfum, it is somewhat ironic that Flowerbomb exploded, so to speak, coming to define the brand as much as its runway exploits. “What we did know when we started out was that fragrance was a vital element of a fashion brand,” Horsting says. “The vision we had of being a big brand and being famous designers meant you have your own store, you have your collections, you have your fragrances. It was a very romantic, almost naïve, image of the future. But at the same time it was also a very real desire.”

And yet, for a brand in the thrall of art and creativity, this desire did not—could not—translate into the kind of mass penetration expected in the industry today. Even with haute couture on hold for over a decade at the turn of the millennium, Viktor & Rolf stayed resolutely on the surreal side of fashion. Gowns hacked with chainsaws (spring 2010), a show presented upside down and in reverse (spring 2006) and outfits rigged with lights and speakers (autumn 2007). The pair used the autumn 2008 collection to protest against fast fashion, with tailoring screaming ‘NO’ in three dimensions. For all Viktor & Rolf’s longing to fit into the industry, they seemed terribly anti-fashion in their approach. “Maybe I wouldn’t call it anti-fashion,” Horsting counters. “But, well, maybe I would. It’s true that we like to do things our own way and in our own time and at our own pace.”

That much is clear: they returned to couture on their 20th anniversary after 13 long years away and they resisted the temptation to release a slew of fragrances in the wake of Flowerbomb’s runaway success (Bonbon joined its scented sister only last year). As the artistic pull brings Viktor & Rolf full circle in their pursuit of fashion design at its highest level, Horsting believes bridging art with commerce is no easier for them now than it was in the ’90s.“I think one of the characteristics of our work is that we take a step back, a bit outside of the system. We look at it; we reflect on it, sometimes it’s also the inspiration for our work. And on the other hand, obviously, we’re also very much a part of it,” he says. “But to strike a balance? It’s a challenge, absolutely.”

The latest evolution of the brand comes in no small part from Diesel founder Renzo Rosso taking a controlling stake in the business in 2008 via his OTB Group. The designers were impressed by Russo’s guidance of another high-concept fashion house that has managed to thrive under his stewardship, Maison Margiela. “That has been a very important decision in terms of realising who are we and what is it that we really want to do, what is it that we’re good at,” Horsting says. “Which is … let’s call it the art of fashion. So that’s why we decided to focus on that. The journey towards that decision has taken a while.”

On the question of whether the industry has lost a sense of theatre, Horsting is philosophical. It may be less exuberant, he concedes, but it’s a different time—fashion is a serious business that demands wearability. “I don’t think there’s a lot of interest in poetry, let’s put it that way,” he says diplomatically. That the two friends are in a position to pursue their own poetic inclinations is a testament to the legacy they have created. Whatever the future holds, there’s no question they will face it as one.

“We make each other laugh, that’s important,” Horsting says, reflecting on the partnership. “Being together for such a long time also means we’ve had the same experiences, so there’s almost a private language that we share. We have in-jokes, but it’s also a visual language we’ve developed. When we want to create something, we don’t need to explain very much to each other … because what we’ve created, we’ve created together.

This article first appeared in the September issue of L’Officiel

Subscribe now

No comment yet, add your voice below!